Whose History is Migrant Community History? An Essential Question for Heritage Preservation

I wrote this reflection for one of my favourite blogs, Active History:

Finnish settler woman and two young children in British Columbia circa 1900. Photo courtesy of the Varpu Lindström Collection at the Migration Institute of Finland Archives.

On March 2, 2023, Finlandia University in Hancock, Michigan, announced that it was closing. Since its establishment in 1896 by Finnish migrant-settlers as Suomi College, Finlandia University has been a center of Finnish history and heritage in North America. It has been home to an active Finnish & Nordic Studies undergraduate program and unparalleled archival collections, programming, and a national Finnish-American newspaper through its Finnish American Heritage Center. The news of the closure immediately flooded Finnish communities in the United States, Canada, Finland, and elsewhere.

Finlandia University’s closure marks the latest major loss for the Finnish North American community. For example, the historic Finnish Labour Temple, the heart of Thunder Bay’s – and arguably Canada’s – Finnish community, was destroyed by fire in December 2021, not long after financial crisis led to its purchase by a condominium developer.

When the Finlandia Association of Thunder Bay was forced into bankruptcy, grassroots efforts quickly set out to raise funds to buy the Finnish Labour Temple in order to keep it in community hands. Though the broader community proclaimed its love for the hall and particularly its restaurant, Hoito, sufficient funds were not raised. In the case of Finlandia University, the fate of the university, including the Finnish & Nordic Studies program, faculty, and staff, was sealed. Yet, the Finnish American Heritage Center (FAHC) was saved thanks to quick and decisive action by Finlandia Foundation National.

(Side note: Yes, there are three different Finlandias in this story for which we can thank Finnish national(ist) composer Jean Sibelius!)

As the leading organization for supporting Finnish history, culture, and scholarship in the United States, Finlandia Foundation was fortunately in the position to take the first steps to secure the staff and assets of the Finnish American Heritage Center’s archives, artifacts, art gallery, folk school, Finnish American Reporter newspaper, museum, and bookstore. Finlandia Foundation’s action is particularly remarkable because very few, if any, communities or community-based organizations could have done the same. However, while these heritage assets are saved from auction or the dumpster (where many of the Finnish Labour Temple’s treasures wound up), much work remains to be done to ensure that they are accessible to all and that the FAHC is able to keep meeting Finnish North American and local community needs for years to come.

The main building of Suomi College, later Finlandia University, in Hancock, Michigan. Photo from the Migration Institute of Finland Archives.

This current situation emphasizes the urgent need to meaningfully think through our relationships with heritage, history, and identity and to find new solutions to practical questions of sustainable infrastructure and funding – all issues that reach far beyond the Finnish community. As a historian of Finnish life in North America and also as a Finnish Canadian, I have closely followed the significant shifts happening in historic migrant-settler communities across Canada and the United States in the last years. In September 2020, I wrote for Active History about my grief for the loss of the Finnish Labour Temple and its repercussions for community and history. As I continue to witness, hold space for, and reflect on closure after (fore)closure of ethnic heritage spaces and institutions, it seems there is an essential question we need to tackle: Whose history is migrant community history?

Though the answer is not straightforward, by seriously exploring this question, we can better understand the ways migrant community heritages are entangled in multiple local, national, and transnational histories. These entanglements have resulted in an ongoing awkward positioning of migrant-settler community histories as simultaneously too local and too transnational, and a failure to properly situate them within the regional, national, and global contexts they are part of.

Here, I will use the example of Finnish communities in North America to introduce just a few reasons (out of many) why it is time to integrate migrant-settler community histories into broader histories and why community archives and spaces are an essential part of this. By turning our attention to these issues, I hope we can better begin to share the weight of their preservation.

Despite decades of research conducted in Finland, the United States, and Canada, the histories of Finnish North American communities have found little space within the history of Finland. After the moment of emigration, it seems Finnish migrant history no longer fits in the scope of the national narrative. Instead, it has been boxed into the academic field of “immigration history” or left for the work of genealogists and local historians.

The histories of migrant communities have faced a similar siloing in Canada and the United States, in spite of the intentions of multiculturalism. The social history and multiculturalism movements, particularly from the 1970s onward, allowed migrant-settler communities to assert their historical contributions to nation building to a broader audience. Yet, meaningfully integrating the polyphony of experiences and histories into cohesive, linear national historical narratives proved challenging, and, instead, the “mosaic” of distinct-yet-connected ethnic histories concretized.

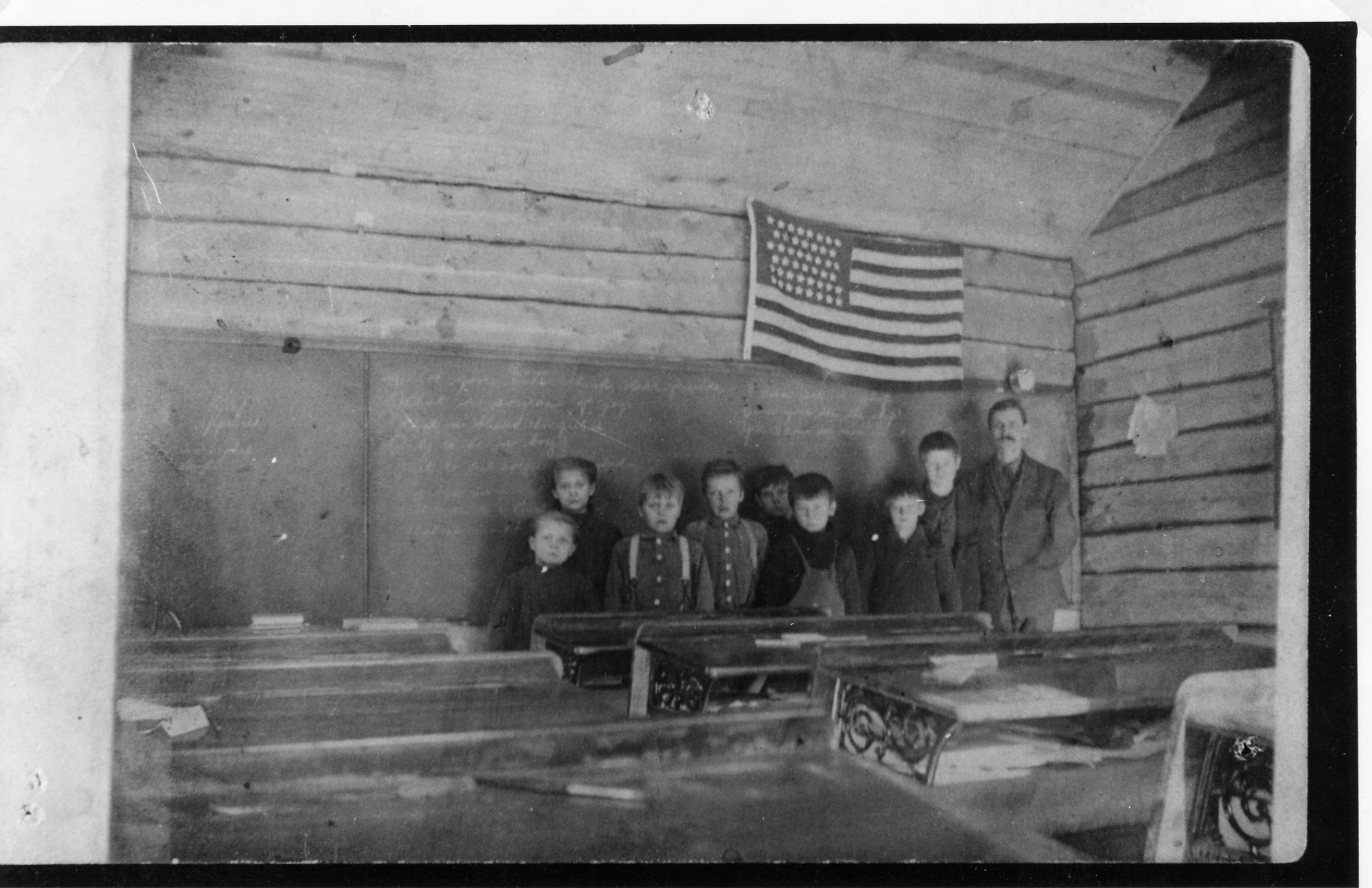

Finnish settler school in Brimson, Minnesota, in 1908. Photo from the Migration Institute of Finland Archive.

Being outside of the purview of the national histories of Finland, Canada, and the United States has meant that migrant-settler communities have been left to shape their own historical narratives. This, in turn, has fuelled the promotion of “pioneer” narratives of “progress” that have relied on a shared North American settler colonial recipe. In such community histories, the view has often been kept so tightly focussed on Finnish migrant-settlers that all wider contexts of time and place have been largely lost.

The reverse can also be true. When tourists and researchers from Finland visit Finnish migrant-settler communities in Canada and the United States, most often they are quick to report back about how they felt as if they had gone into a time capsule. The Finnish culture and language, they exclaim, are from bygone eras and bear little resemblance to modern Finland. Finnish North American communities are framed as a curiosity, quaint and even a bit silly. But viewing Finnish North American culture wholly from a Finland-based lens misses the local and transnational traits and histories that are fundamental to it.

One of the things that makes pinning down migrant community history so difficult is also what makes it so fascinating to study and so valuable to preserve. The cultures, languages, and heritages of migrant-settler communities are not merely transplants but are cultures, languages, and heritages in their own right. They are products of their unique encounters with different places and structures, and reflect strategies for facing challenges. Their histories have timelines that, of course, share much with the timelines of Canada, the United States, and their countries of origin, but also include key moments that are uniquely significant for their own community. The markers of migrant-settler history and heritage demonstrate ongoing negotiations of identity and place.

Take for example “Finglish.” The creation and use of Finnicized English words reflected Finnish migrant-settlers’ encounters with North American job sites, environments, institutions, and cultural customs. Finglish words harken back to the technology, culture, and social order of the time of mass migration in the early twentieth century. If you want to see for yourself, take a look at the North American Finglish dictionary. This hybrid “language” serves as a clear marker of a distinct Finnish North American culture and identity that bridged people’s transnational connections and experiences. Finglish is neither Finnish nor English: it is its own linguistic form.

Many historic migrant-settler communities today are confronting language loss, and the number of Finnish speakers in Canada and the United States has also been decreasing for decades. Yet, I would argue that there is actually even more at stake than the loss of Finnish. In the broader context, the Finnish language is thriving (despite anti-immigrant rhetoric in Finland), but with each passing North American Finglish speaker, this unique dialect is in danger of disappearing from oral tradition.

Finglish and its counterparts from other migrant groups should be taken seriously as North American intangible heritage. These migrant community linguistic forms have much to teach us about our shared history. Community halls and heritage events are crucial sites for maintaining these “languages”. When we lose these migrant community spaces, we also further attenuate the position of these unique linguistic hybrids.

Fortunately, these dialects and the lives and worldviews of the people who constructed them can also be found in migrant community archives – if we take their holdings and preservation seriously. The archives reveal how migrant communities claimed place and belonging in Canada and the United States. This was done in part through language, narratives, and naming practices, but also physically through clearing lands, and constructing homesteads and community spaces. In all of these actions and the archival collections established to document them, we see the creation of migrant community history. These histories are solidified through the production of family histories, local histories, and organizational histories, and through community heritage work, such as monumentalizing the collective past.

Finn Road in rural Timmins, Ontario. Photo by Samira Saramo.

As we work on unsettling the legacies and disrupting the ongoing harm of settler colonialism in Canada and the United States, migrant community archives and spaces offer concrete examples of the everyday place-making that contribute to structures of dispossession and inequity. With every story of overcoming wilderness through tenacious Finnish “sisu”, we find the symbols and strategies of claiming place but also the potential tools for calling these to question. With every rural Finn Road marker, we find a trace of Finnish involvement in the settler colonial project and a tangible way to demonstrate how Indigenous displacement is enacted and legitimated through such acts.

The histories contained in migrant archives and community spaces offer important pieces to understanding the working of settler colonialism in the projects of building the Canadian and U.S. nation-states. Likewise, migrant histories can demonstrate the colonial involvements and complicities of the countries of origin. For example, Finland, like the rest of the Nordic countries, has only recently even begun to acknowledge that it has a history of colonialism. While many remain closed to meaningfully understanding and addressing the serious repercussions of Finnish settlement and ongoing resource extraction in Sápmi, the Sámi lands in the north, the history of Finnish settlement in North America may offer an easier entry to unpacking colonial participation.

A failure to recognize that migrant community histories are part of broader, collective history results in missed opportunities to build our understanding of the past and its connections to today. By continuing to insist through inaction that the preservation of migrant community heritage spaces and archives should rest solely on the shoulders of small, aging, and often economically strained “ethnic” communities, we perpetuate the message that migrants are of “neither here nor there.” This, in turn, can have repercussions on integration work and emigrant support in an increasingly mobile world. When we inevitably next face news of another migrant community heritage site struggling to stay afloat, I urge you to think about whose history is really at stake.

Further Reading

Rani-Henrik Andersson and Janne Lahti, editors. Finnish Settler Colonialism in North America: Rethinking Finnish Experiences in Transimperial Spaces. Helsinki: University of Helsinki Press, 2022. Open access: https://hup.fi/site/books/e/10.33134/AHEAD-2/

Donna Gabaccia. “‘Is Everywhere Nowhere?’ Nomads, Nations, and the Immigrant Paradigm of American History” in Journal of American History 86, 3 (December 1999): 1115-1134.

Laura Madokoro, “On future research directions: Temporality and permanency in the study of migration and settler colonialism in Canada,” History Compass 17(1) (2019): 1-6.

Samira Saramo. “Terveisiä: A Century of Finnish Immigrant Letters from Canada” in Hard Work Conquers All: The Finnish Experience in Canada, eds. Michel Beaulieu, Ronald Harpelle, and David Ratz, 165–184. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2018.