TORONTO

Tkaronto

Tkaronto, the land that is now most-often called Toronto, has been the site of human activity for at least 15 000 years. The City of Toronto acknowledges that it “is the traditional territory of many nations including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples and is now home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. We also acknowledge that Toronto is covered by Treaty 13 with the Mississaugas of the Credit.”

To become familiarized with the Indigenous history of the Toronto area and the Treaties and Agreements that govern it, check out:

and

This Toronto Land Acknowledgement Poem video by Lena Recollet is from the multimedia resources of the Whose Land website.

Toronto as a Center of Settler Colonial Power

Toronto solidified its place as a colonial center with its naming as the capital of the new Province of Ontario, following Canadian Confederation in 1867. The city’s growth was directly ties to Canada’s colonial expansion westward and the development of resource extraction. Toronto became Canada’s finance center.

Migrants provided essential labour to fuel the city’s growing manufacturing and commercial sectors, and to meet the service needs of the rising wealthy middle-class.

For an overivew of Toronto’s history, see:

Finnish settlement in Toronto

In 1887, the first known Finn to settle in Toronto arrived. James Lindala successfully recruited other Finnish tailors and their families to come to the city, and by 1900, a small, closely-knit Finnish community had formed.

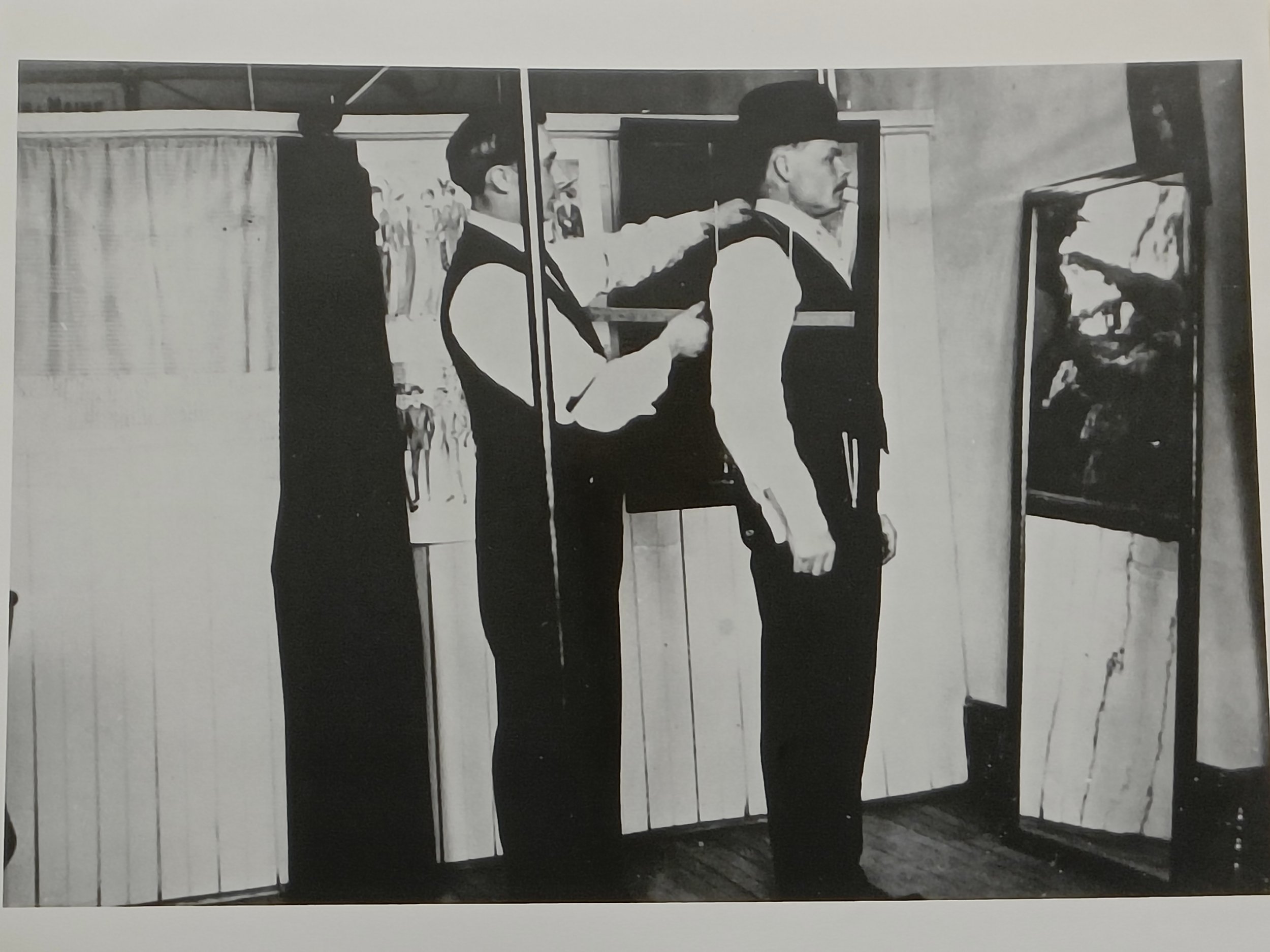

The heart of the Finnish community became the Lindala’s tailoring workshop “Iso-Paja” at 159 York Street. In 1903 “this coperateively run shop had room for fifty tailors who could rent space and the use of machines for 25 cents per week, and work in an atmosphere of camaraderie. All had to join the Journeymen Tailors’ Union, and socialist doctrines were actively promoted at Iso-Paja. The tailors listened to selections from working-class papers and socialist literature… read by a paid reader during the busy times and by one of the tailors during the slower season. In the front of the store Mrs. Lindala sold groceries, and downstairs there was a large public sauna” (Lindström, 9-10). Lindala was the de facto head of the community and his workshop served as the community center before a separate Finnish social space was established.

The skilled trade background of the early Toronto community is quite unusual in the broader context of Finnish settlement at the turn of the century.

However, in the first decades of the 20th century, many Finnish women also came to Toronto to work as domestic servants. As the community grew, naturally the fields of employment also grew into many industries for men and women alike.

The big city offered opportunities but also many risks and dangers for young migrants, especially single women working in service.

The community settled around Iso-Paja between Richmond and Adelaide, but also nearby in Kensington Market and in “the Ward” (St. John’s Ward) known as a common landing area of many new immigrants to the city.

With time, the Finnish community grew and diversified. The increasingly wealthy early Finnish settlers bought homes further north in the city in more affluent areas.

Further Reading:

Varpu Lindström, The Finnish Immigrant Community of Toronto, 1887-1913 (MHSO, 1979).

Jenni Stammeier, Tyttö maissi pellossa - Anna Jokisen mysteerikuolema (Docendo, 2022)

The former site of Iso-Paja in 2023.

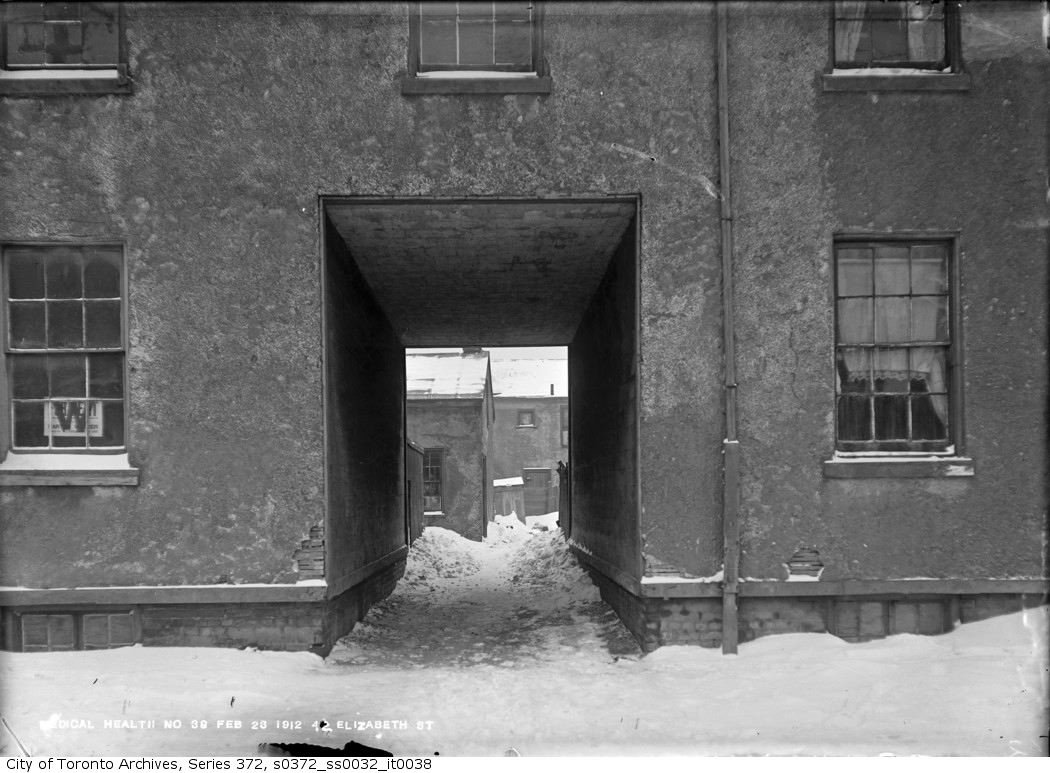

These photos were taken by the City of Toronto’s Department of Health in February 1912 to document housing and sanitation. They show places that were part of Toronto’s “Finntown.” While the photographer was aiming to depict these places as immigrant “slums”, we can look into the courtyards and alleys and imagine the bustle of daily life.

This map was marked by Varpu Lindström in the late 1970s as she researched the history of the first Finns in Toronto at the turn of the 20th century. It is now available in her archival fonds at the Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections at York University. In August 2022, I followed the map of my belated dear mentor, photographing and recording the sounds of these places.

These soundscapes and photographs are from 100 years after the images above. Little remains of the neighbourhood that was once the center of the Finnish community of Toronto.

Finnish Toronto Today

Toronto’s Finnish community’s main presence is now in the north of city, where Finnish churches, organizations, a credit union, and foods can be found. In York Mills, most Finnish activity centers on Agricola Finnish Lutheran Church and Suomi-Koti Toronto, a retirement and care home. The active Finnish Language School (Toronton Suomenkielen koulu) and other Finnish clubs utilize Agricola’s space for their programming.

Not far from the original Finntown, the University of Toronto’s Finnish Studies Program offers Finnish language and culture courses. The University’s Hart House is also a regular site for events of Toronto’s Canadian Friends of Finland organization.

Toronto still boasts being home to the second most Finns and Finnish descendants in Canada. Unlike many historical centers of Finnish settlement, where migration from Finland has all but stopped, Toronto continuously welcomes new Finns. These new migrants are typically highly educated and come due to employment, education, or spouses.

This map shows the locations of the most active Finns community sites in Toronto today:

Changing Toronto

This wonderful openly accessible tool allows maps from different moments of Toronto’s history to be layered. Honing in on the area that had the highest concentration of Finns in the early twentieth century, bordered by Queen West and Adelaide and Peter and York, shows radical changes.